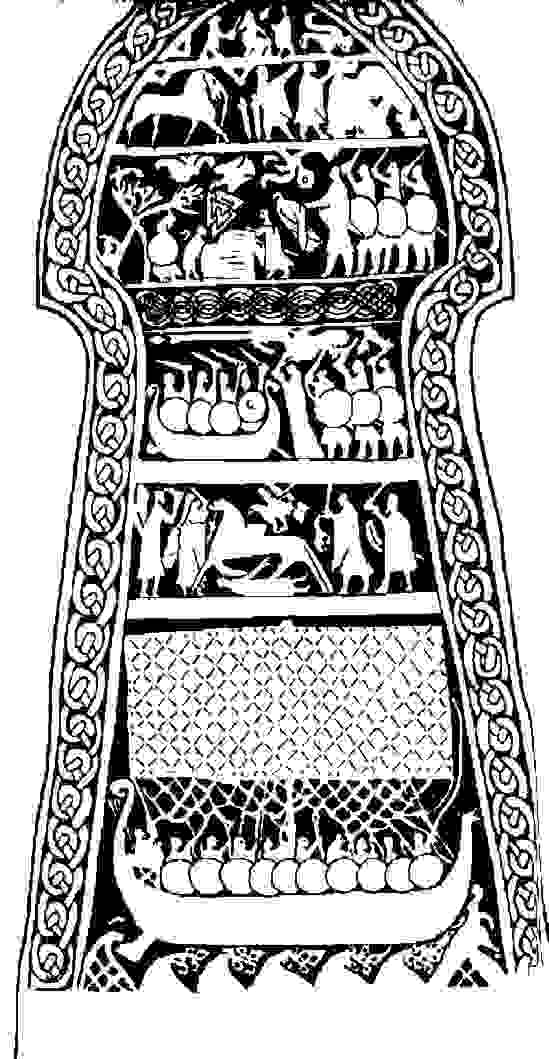

Runic inscription (based on the first Futhark), norwegian Gokstadskipet

The Gokstad Longship

This article is dedicated to my friends in Bergen, Norway, the ancestral homeland of the vikings .

From the maiden's bower I hear

Secret sighs, these

Shall not be wasted.

I love her words,

Though I cannot see her;

Let everybody know

How highly I praise her friendship.

(19., the history of King Magnus Barefoot. Heimskringla. S.Sturlason)

Some interesting engraved stones from Gotland Island, Sweden, providing details on the scandinavian rigging. From left to right: Lärbro stone,Stenkyrka stone, the stone from Broa in Halla, and one notdentified stone.

Excerpt from Egil's Saga

The Ship:

Vikings and their Ships. Overview

The viking long ship (Langskipet ) excelled during mid IX century. Back then, the scandinavians had evolved from their oar driven coastal vessels Faering (small rowing boat) used to move within the fjords, to the sail propelled keeled versions, the many subtypes of which were the Karv (coastal vessel), Knarr or Knörr (cargo or merchant ship), Drakkar and Snekkar (also called Skeid(*), fighting vessels). With these, specially with the bigger oceanic type, the Skeid, they moved out to far places, in a "hoping islands" fashion, reaching Iceland, Greenland and ultimately the so called Vinland (Leif Eriksson's Saga) which we today consider was in fact North America (pls see "Before Columbus?" below).

(*) Skeid: According to Snorre's Heimskringla, the Skeids were built on specially fine lines, and were swifter than other vessels. Sometimes they didn't wear a dragon head. We consider them derivative of the Snekkars. Following this criterium, the Oseberg ship which indeed was a Snekkar judging from the serpent head which was found within the rests and allowed to be reconstructed, must have been a Skeid, thanks to its slender lines. Some naval specialists think it was very small, and therefore a Karv.

We have learnt to identify these ships as holding rows of shields hung from the gunwales, and terrifying dragon or sea monster heads as figureheads on the bows. But such ornaments had specific uses even determined by their local laws. In fact, the shields (which were hung using strings) were exposed only on certain ceremonial occasions, and would have surely been washed away by any mid size open water wave. As for the figureheads, they were never used on friendly areas: They were intended to intimidate enemies during raids or naval battles. Using them in home waters would have "scared away" friendly spirits.

The vikings did not know the compass or magnetic needle, but they sailed with astonishing (or at least practical) accuracy.They usually passed on the information on currents, landfalls etc. Also, they relied on a sort of graduated sundial by means of which they could determine the height of the sun and fix an approximate position. On certain special occasions, mostly when it was cloudy for a long time (as it normally appears to be in northern latitudes) they would exceptionally use a kind of special light polarizing crystal or sunstone. Light passing through the stone would turn from yellowish to blueish when perpendicular to the sun rays, thus allowing to set the angle, even when not directly receiving the rays.

But, they indeed attained high specialty in the construction of their perfectly suited ships, and in the sailing techniques. They could sail into the wind holding the windward edge of the big square sail by means of a special spar or long pole, a boom, they called Beitass. This spar rested on the low deck on a special foot plate or chock with two depressions to avoid slipping. It disappeared later, when the bowlines were developed.

A word on the construction techniques, and rigging:

For the ocean-going, later types, they would lay the "T" shaped keel, add the massive stern and stem. The hull was then assembled from the clinker straked sides, later "U" shaped ribs and beams. The fixing of the strakes succeeded using small blocks and sinew ties. This provided a spectacular, much needed flexibility to the hull. A massive mast foot of peculiar shape with a slot and blocking wedge was used to hold the mast upright.

As for the rigging, we have already mentioned that bowlines were not used. The great sail was strengthened by means of a crosswork of bridles, later hanging like net sheets, by means of which the sail's foot was held evenly. Although a great number of blocks was found within the Gokstad burial mound, the ropes had rotted away, so its function within the rigging is uncertain.

There were also three poles with crossbars, that were probably used to rest the sail spar, when this was not hoisted.

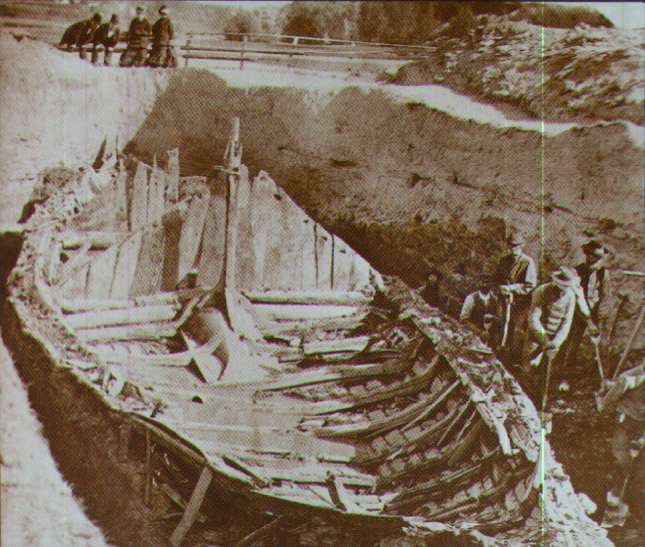

The Gokstad ship:

This unique ship was found within a blue clay tumulus in Gokstad, Sandar, Sandefjord, Oslo in 1880. It was part of the burial of a wealthy man around his fifties/sixties. (assumed to be Olav Geirstader-Alv, stepson to Queen Aasa). The ship measures 23 mtrs from stem to stern and is 5,20 mtrs broad. Maximum height from keel to upper gunwale is approximately 2 mtrs. It had room for 16 pairs of oars, therefore being rowed by 32 men. Ship sides are built with 16 strakes, the 9 lower of which are 2,3 cm thick, the 10th is thicker (4,3 cm) being the hull's reinforcement. 14th strake is also sturdier, because it holds the oar lock-holes. Keel, mast boss and strakes are made of oak, mast and deck planking of pine.

The famous skandinavian rudder, the stjorbordi, was rigged up the right side. Made firm by a grommeted "rope" (pine root sinew) to an oak boss, the upper part was tied with ropes through two holes in the gunwale. A tiller, perpendicular to the rudder shaft, permitted steering. A ring on the blade allowed for a rope to be used to hoist the rudder, when the grommeted rope was slackened, thus allowing to sail/row the craft even on shallow waters.

The findings at L'Anse aux Meadows, a site on the northwest coast of the island of New Foundland, (1973/77) have confirmed norwegian presence in America, before Columbus. Bitchbark objects, clinker and charcoal, excavated from peat bogs were radio-carbon dated to the A.D. 860-90 and 1060-70.

Also, the remains of typical viking comunal turf houses were unearthed, although they lacked the normal stone foundations, and had not been repaired, thus pointing out to an occupation period shorter than, or around 25 years.

Thus, the exploits of Leif Eriksson , as explained in the corresponding Saga, have been confirmed. Leif spent a winter there, being attacked by the Skraelings ('ugly men', the american indians) Later his brother Thorvald set for Vinland only to fall later to an indian's arrow shot. Finally a merchant named Thorfinn Karlsefni, married to Gudrid, a stepdaughter of Leif, went to Vinland but after three winters there, concluded that a settlement was not feasible. It is also important to note that Gudrid gave birth there to a child, who they named Snorre, thus being the first European-american of the history.

The Model:

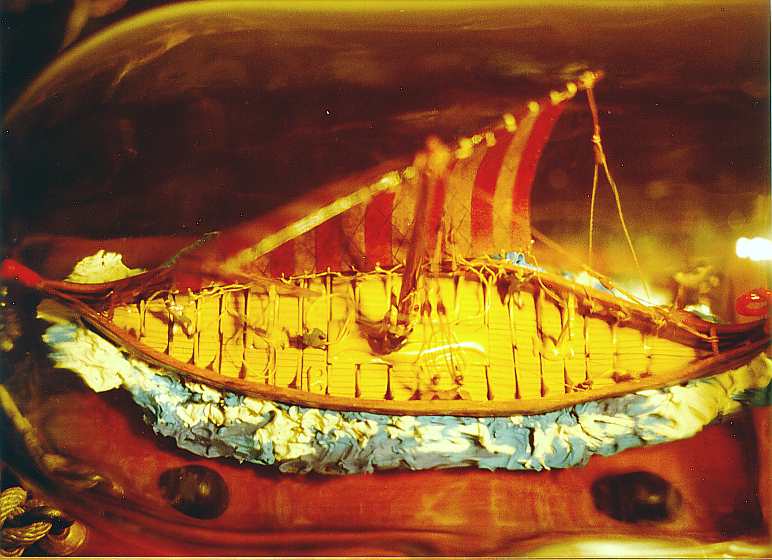

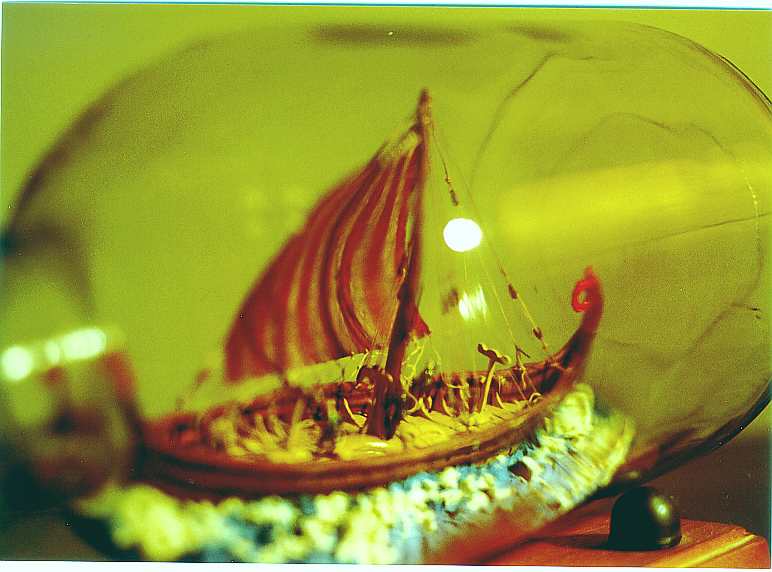

In this sea bird's eye view of the model, high above mast's top, we see her battling against rough seas. She is taking the waves valiantly, while beating to windward taking the wind by the port bow quarter, keeping the sail taut by means of the beitass. We see the crew busy with the running rigging. The deck planking is clearly exposed, the thwarts, and the massive mast boss. The hull had to be split into 6 parts and reassembled inside the bottle. Regrettably, the industrially blown bottle does not honour the visibility of the model.

Port, quarter bow view of the ship. Clearly visible is here the aft pole and crossbar, used to support the main sail spar, when lowered.

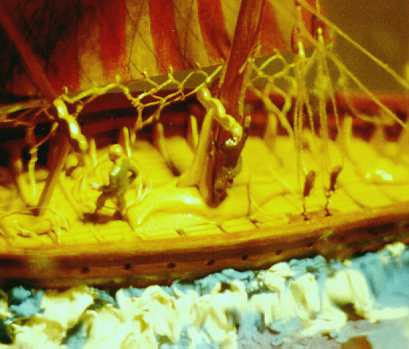

Close up showing the fore spar pole and the main spar pole. A crew member is busy with the leech bridles of the main sail. As for the mast shrouds, we have followed the speculative adaptation of the deadman eyes found within the burial, suggested by Mr Landström.

Starboard broadside close-up view. Clearly visible is the elaborated sail foot bridle network. Also visible are the oar locks or holes. Please note these would normally be closed by means of small wooden caps. The strakes have been intermitently darkened. This stripe work is to be seen in the ships depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry. We can also see the speculative fore main stay tackle rigging.

Due to a deformation of the bottle glass, the hull seems to be gently curving with the waves. Although this is an optical trick, the real hulls were indeed very flexible due to the construction technique.

Some famous Longships:

The Long Serpent (Ormrinn Langi, Orm=snake akin to worm, vermi): Vessel of King Olav Trygvason. Made after the Serpent which Olav brought from Halogaland. It was indeed a Drakkar. His stemshipwright was Torberg. She had 34 rooms (68 rowing seats), and was the costliest and best fitted longship ever built in Norway.

This ship engaged in the famous battle of the Svold, against the fleet of Swein (danish king), Olav the Swede and Eric the Jarl.

Ormrinn Lange, lashed together with other fighting vessels, the Short Serpent and the Crane(30 rooms) was finally boarded and captured after a fierce fighting, by Eric the Jarl. Olav jumped overboard, and was reportedly dead.

Other famous vessels of King Olav were the Carlshead and the Visund (bison).

King's canute Dragon: A phantom Drakkar having 60 rooms.

The Mora: Flagship of William the Conqueror, had a dragon's head on the prow and a trumpet blowing herald on the stern. It had a gilded weather vane or perhaps a lantern on top of the mast.

To read the same article in german, please follow the link Das Gokstad Langschiff

Bibliography:

Heimskringla or The Lives of Norse Kings, Snorre Sturlason, Viking Ships Findings, Universitetets Oldsaksamling Oslo,The Vikings, Lords of the Seas, Yves Cohat,The Ship - Björn Landström. Runes taken from First Futhark, The Book of Old Ships, Henry B.Culver, Historische Schiffsmodelle. W. zu Mondfeld, Eyewitness: Boats, Dorling Kindersley. The Visual Dictionary of Ships and Sailing,Dorling Kindersley. Las Artes de la Mar. Enciclop. Gráfica Ilust.,Tre Tryckare, National Geographic Magazine.(Atlas and various issues).

Note: The background art of this page, representing mytical scandinavian beasts was taken from the richly decorated wood cuts of the prow of the Oseberg ship.

(c) 1998-2020 Eduardo Raffaelli. Buenos Aires . Argentina